It always surprises me that there are certain things in my life that I return to, over and over again. I suppose I really shouldn’t find it so astonishing — given that I do come back to them, repeatedly, and without fail. But when I do revisit something from the past, usually from my childhood, I feel like I have stumbled into some kind of magical world.

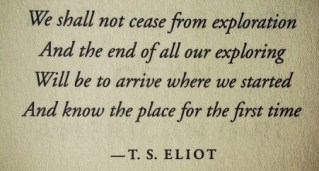

There is a subtle sense of homecoming in such moments, something that always calls to mind T S Eliot’s lines from Little Gidding:

Eliot’s poetry is one thing that I periodically return to. Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea books are another. And lately, I have come back, once again, to classical music.

I have mentioned before that I grew up in a household where classical music reigned supreme, with a small smattering of jazz thrown in every now and then (most often on the weekends). My parents always supported me musically, and as a child I learned to play the violin, piano, and flute reasonably well. I even got pretty good at the recorder — a bit beyond your average dribble-stick Hot Cross Buns playing primary school student repertoire — and played either descant or treble in a recorder quartet.

I have mentioned before that I grew up in a household where classical music reigned supreme, with a small smattering of jazz thrown in every now and then (most often on the weekends). My parents always supported me musically, and as a child I learned to play the violin, piano, and flute reasonably well. I even got pretty good at the recorder — a bit beyond your average dribble-stick Hot Cross Buns playing primary school student repertoire — and played either descant or treble in a recorder quartet.

Later, with the encouragement of a wonderful teacher who let me take home various school instruments over the holidays, I taught myself clarinet. That teacher was always challenging me, inviting me to audition for an all city concert band I never thought I would get into, then pushing me further by naming me Principal Flute player of that ensemble — never doubting that I was capable of leading my section — and handing me a piccolo, which I’d never played before, with an offhand remark along the lines of, “Don’t worry, you’ll pick it up in no time; just get yourself a book of Irish folk tunes and you’ll be fine.”

Later, with the encouragement of a wonderful teacher who let me take home various school instruments over the holidays, I taught myself clarinet. That teacher was always challenging me, inviting me to audition for an all city concert band I never thought I would get into, then pushing me further by naming me Principal Flute player of that ensemble — never doubting that I was capable of leading my section — and handing me a piccolo, which I’d never played before, with an offhand remark along the lines of, “Don’t worry, you’ll pick it up in no time; just get yourself a book of Irish folk tunes and you’ll be fine.”

Perhaps this is why classical music feels like home to me, and that I come back to it time and again: for me, it is associated with people who have supported me, had my back, and treated me with the assumption that I would succeed.

As I write this, I am listening to Nigel Kennedy’s recording of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending. It is familiar, it is comforting. And, to me, it is not merely beautiful — it is sublime.

It is also solace, and an entry into an ethereal world: a place of soaring, sprialling birdsong, of tangled hedgerows and verdant meadows, of arching blue skies and gentle summer breezes.

If you’d like to hear it yourself, you can listen to it here, and fly away.

The Ancient Greeks, it seems to me, knew stuff.

The Ancient Greeks, it seems to me, knew stuff. But there is a catch.

But there is a catch. Anyone who creates regularly and deliberately will tell you that yes, there are those fabled golden moments when whatever you are creating flows from you effortlessly. They are magical moments, and I do mean that literally. But the point is you have to be there, already creating, for those moments to happen. And no one can do that for you. You have to have the courage to do it for yourself.

Anyone who creates regularly and deliberately will tell you that yes, there are those fabled golden moments when whatever you are creating flows from you effortlessly. They are magical moments, and I do mean that literally. But the point is you have to be there, already creating, for those moments to happen. And no one can do that for you. You have to have the courage to do it for yourself. Listen to that funny little guardian spirit — the one who has either been waiting patiently for you, or has been yammering away at you to do something for so long that it might just fall off your shoulder in shock when you finally pick up that paintbrush, or write that poem, or sew that dress.

Listen to that funny little guardian spirit — the one who has either been waiting patiently for you, or has been yammering away at you to do something for so long that it might just fall off your shoulder in shock when you finally pick up that paintbrush, or write that poem, or sew that dress.