It’s been ages since I wrote, which usually means I need to get how I am feeling about whatever is happening to my dear old Dad out of my system. The Professor had a birthday last month, so is now heading towards his mid-eighties…not that Alzheimer’s Disease will let him remember that.

Or much else, for that matter.

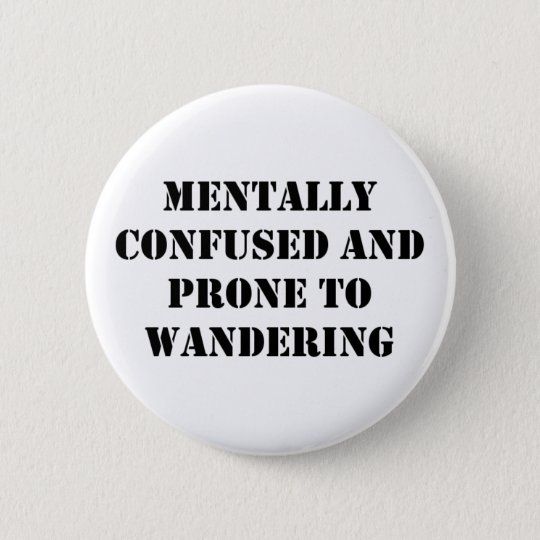

Every now and then I feel weirdly guilty about the time when my brother and I gave Dad one of those birthday cards with a badge attached — the one we picked was one bright orange with navy blue writing, and said “Mentally Confused and Prone to Wandering”. Our then-teenaged selves never once suspected he might actually need such an accoutrement: to us, Dad was so incredibly whip smart and intellectually beyond us that such a thought was ludicrous, particularly as he was then working at the dizzying heights of academia. We made him wear it to the Ivory Tower he worked at, a university which later granted him a PhD after he completed all the course work, oral and written examinations in three languages, his dissertation and his thesis defence in just under two and a half years. All while financially supporting his family.

We thought making Dad wearing the badge to work was absolutely hilarious.

Mentally confused and prone to wandering? Pfft…

And now, several decades later, The Professor is exactly that.

Seven years ago, when he was first diagnosed with dementia, if you did not know The Professor you would have been hard pressed to recognise the signs and symptoms that had alerted us to the fact that all was not well. And now, after years of gradual decline, the past twelve months have produced an accelerating deterioration of his condition.

Even so, The Professor is trying to retain his dignity while his world is so utterly, heartbreakingly diminished.

The man who we would constantly have to ask to slow down when he strode briskly ahead of us now moves unsteadily, and at a glacial pace.

A year ago, crossword puzzles delighted him…but then they became more difficult. He started looking up answers in the back of the book and filling them in. Then those answers became confused, or mis-spelled, or entered into the wrong squares. Now the whole concept is beyond him.

Spoken words, which were once a source of great enjoyment for him — let’s be honest, The Professor was literally a lecturer, both at work and at home — have all but disappeared. He now prefers to use hand gestures and facial expressions to communicate what he wants (or, increasingly, what he doesn’t want). His verbal communication is limited at best, and we have to remind him to use his words.

Use your words.

I thought my days of saying that phrase ended around the time when my children started school.

Turns out I was wrong about that, too.

I haven’t heard him say my name in a long time, and many times when we meet up I can see he has no clear idea who I am. He seems to know, however, that I am someone who loves him, and who is not is going to threaten or harm him in any way.

And so, we take refuge in humour.

If I do end up having a phone conversation with The Professor, which is now almost exclusively one-sided, I try to make him laugh. If we’re on FaceTime, I’ll settle for a smile — or a hint of recognition that he has got whatever joke I’m attempting to make.

My mother, who would definitely win the Nobel Prize for Caregiving if there was such a thing, is still looking after The Professor in their home. I honestly don’t know how sustainable that arrangement will be if he continues to decline, but given it’s something she is currently committed to, I am attempting to support her however I can. We used to try to make light of The Professor letting the (indoor) cat out, but now we’ve been reduced to joking about not letting The Professor out.

The whole situation is unsettling and confusing and seemingly never-ending, but evidently The Professor is not yet ready to leave us.

I suspect I will be more than ready when he does.

That is one thing a diagnosis like The Professor’s gives you: an extended period of time in which to grieve.

And I can honestly say I do not write about this to garner sympathy or attention for myself. Writing enables me to make sense of what I am feeling about a complicated situation, one which I am resigned to and accepting of (even though it absolutely sucks). While these are my words, they are about and for my father, who genuinely deserves all the compassion and consideration in the world.

I choose to write publicly about my experiences to acknowledge and provide a window into The Professor’s ever-shrinking world. To remind my teenaged self that the badge my brother and I gave our Dad was intended, and taken, as a joke — and one we all laughed long and hard at. To give my mother something to refer people to if their questions or kindnesses make it too hard for her to respond. To use my words to tell The Professor’s story now he is unable to tell his own.

So, if you’re reading this, please remember — for as long as your brain allows you to remember — to LIVE!

Live freely, love fiercely, choose wisely and make every single day count.

BJx